|

Everyone needs a subculture to call their own. This is ours: Americans who

play traditional music from Bulgaria, Macedonia,

Croatia, Serbia,

Greece and Albania.

And people in America who dance to it, both émigrés and Americans.

It's not a purely American phenomenon, of course: There are people

like us all over the world -- foreigners who play Balkan music.

Balkanarama 1999-2000, the lineup for our first CD: Clockwise from top left, Tym

Parsons, Fred Graves, Mike Gordon, Matty Noble, Kathleen Hunt, Sue Niemann, Jody Levinson, Kathy

Sandstrom. Photo: Eric Perret.

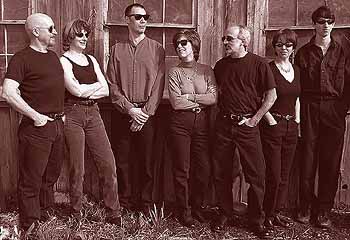

Balkanarama 2000-2003, the lineup

for our second CD: L-R: Matty Noble, Tym Parsons, Fred Graves, Jana Rickel,

Jody Levinson, Mike Gordon, Sue Niemann.

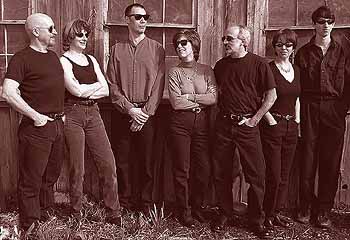

Balkanarama 2003- : L-R, Mike Gordon, Jana Rickel, Tym Parsons, Jody Levinson, Fred Graves,

Sue Niemann, Matty Noble. Photo: Abraham McClurg.

|

Why play music from a different culture?

In some ways, Balkan dance music is akin to American rock 'n' roll: It

represents a fusion of multiple cultures. In America, it was black R&B

colliding with white musicians. In the Balkans, it was Slavic and other

native traditions

colliding with Rom and Ottoman influences. And it may be no accident that in both

cases, the best music -- OK, the music we like best -- was made by the people who got the worst of the

cultural encounter.Many of the songs we play come from the Balkan Roma, the

people once called Gypsies, who were

enslaved in Romania for as long as blacks were in America. In both countries,

an underclass gave birth to the dominant strain of popular music. The Rom

sound is as popular in southeastern Europe today as black music is in the

West.

If you've been raised on a

steady diet of Western pop, Balkan music takes getting used to. It's a

little like klezmer after a couple of shots of Turkish coffee.

While many of our favorite tunes use familar rhythms -- including the driving

rhumba beat called chochek or kjuchek -- some Balkan tunes add spice by using asymmetrical

meters like 5/8, 7/8,

9/8, 11/8, 13/8, 15/8, 18/8, 22/8, 25/8 and beyond. We've recorded a few --

you can hear samples.

The music is half the

story -- the co-performers in the audience is the rest. There are thousands of Americans who've learned

a polyglot vocabulary of Balkan dances and do them together for fun. Half our

musicians started out as Balkan dancers. The steps can be hypnotically simple or maddeningly complex. Most are line dances

-- few are done in couples. Our taste runs to simple, generic dances that

can be done to many different songs, rather than the complex "folk" choreographies from

the repertoire of performing groups or itinerant dance teachers.

What does the music sound like? Depends on where you go.

In

Hungary and Romania, it sounds like a string quartet on steroids: violin

dance melodies and mournful ballads, driven by a powerful rhythm section. In

Croatia and Serbia, there's the tamburica tradition of plucked-string

instruments a lot like the mandolin orchestras popular in the U.S. a couple

generations ago. All over the area, there are brass bands and urban

orchestras using accordion, violin and woodwinds. From farther south, in

Bulgaria, Macedonia, Albania and Greece, come wailing melodies by Rom

wedding bands that play songs popular across the region, mostly on modern instruments

these days, increasingly with a jazz flavor. What does the music sound like? Depends on where you go.

In

Hungary and Romania, it sounds like a string quartet on steroids: violin

dance melodies and mournful ballads, driven by a powerful rhythm section. In

Croatia and Serbia, there's the tamburica tradition of plucked-string

instruments a lot like the mandolin orchestras popular in the U.S. a couple

generations ago. All over the area, there are brass bands and urban

orchestras using accordion, violin and woodwinds. From farther south, in

Bulgaria, Macedonia, Albania and Greece, come wailing melodies by Rom

wedding bands that play songs popular across the region, mostly on modern instruments

these days, increasingly with a jazz flavor. It isn't just the music that draws us in -- it's the people, too. I've

moved across North America twice, and both times, I found a ready-made

community of friends among people who shared this strange passion. If I

moved to New York or San Francisco or Ann Arbor tomorrow, I'd be able to do

the same. What we do together is about as good for you as human activity gets:

Because there's no money involved (ours is a distinctly low-rent

subculture), it's fun, not work. It's a good excuse to party: eat, drink and

burn it off on the dance floor. And,

when musicians play live for dancers, it becomes a mutual conspiracy to raise the energy level in

the room as high as we can.

Which is sometimes pretty high.

-- Mike Gordon

|

What does the music sound like? Depends on where you go.

In

Hungary and Romania, it sounds like a string quartet on steroids: violin

dance melodies and mournful ballads, driven by a powerful rhythm section. In

Croatia and Serbia, there's the tamburica tradition of plucked-string

instruments a lot like the mandolin orchestras popular in the U.S. a couple

generations ago. All over the area, there are brass bands and urban

orchestras using accordion, violin and woodwinds. From farther south, in

Bulgaria, Macedonia, Albania and Greece, come wailing melodies by Rom

wedding bands that play songs popular across the region, mostly on modern instruments

these days, increasingly with a jazz flavor.

What does the music sound like? Depends on where you go.

In

Hungary and Romania, it sounds like a string quartet on steroids: violin

dance melodies and mournful ballads, driven by a powerful rhythm section. In

Croatia and Serbia, there's the tamburica tradition of plucked-string

instruments a lot like the mandolin orchestras popular in the U.S. a couple

generations ago. All over the area, there are brass bands and urban

orchestras using accordion, violin and woodwinds. From farther south, in

Bulgaria, Macedonia, Albania and Greece, come wailing melodies by Rom

wedding bands that play songs popular across the region, mostly on modern instruments

these days, increasingly with a jazz flavor.